|

Wrington at War 1939-45 by Mark Bullen |

|

Wrington at War 1939-45 by Mark Bullen |

| The Background At the outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939, with a population of only about 1500, Wrington was very different to how it is today. In the pre-supermarket era, the village was well served by butchers, boot makers, bakeries and general grocery stores. People could buy radios, cycles and electrical goods and have them repaired in the village. They could hire a car, order their seeds from the local newsagent or even procure a pair of hand-made gloves without having to leave Wrington! With the advent of central heating still decades away, solid fuel provided the main sources of warmth. According to their advertisements in the 1939 Village Journal, Barber Bros. and Thomas Tincknell, both based at Railway Wharf, sold all classes of house coals, coalite smokeless fuel, anthracite “pea-nuts”, best Welsh boiler nuts, graded coke and peat blocks, as well as logs and firewood. Barber Bros. also ran a haulage business, whilst Tincknell doubled up as the local builders’ merchant. There were three village pubs – The Plough, The Golden Lion and The Bell, the last becoming Richards Stores a few years after the end of the war. Land currently occupied by the plethora of housing developments that have sprung up since the war was largely given over to apple orchards and fields, with most houses primarily concentrated around the old village centre.

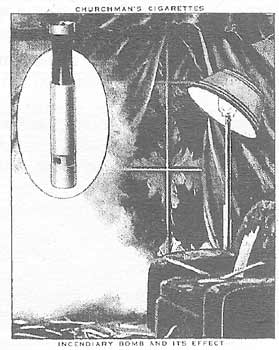

Although it was not exposed to the terrible air raids that destroyed much of central Bristol, like many other west-country villages, it saw its fair share of action. Bombs were dropped, an enemy plane crashed into a field just beyond the churchyard and, like everyone else, Wringtonians had to cope with the everyday difficulties and privations facing the rest of the population. The departure of loved ones to fight in the armed forces, the fear of bombing, possible invasion, the black-out, rationing and the arrival and integration of evacuees, to name but a few issues, all contributed to make life difficult for everyone, rich and poor alike. During the 1930s the Luftwaffe had grown into an awesome force whose aircraft were capable of carrying out heavy bombing of Britain at will. Later on, Germany’s occupation of France gave her possession of airfields very close to the southern coast of England. Above all, this meant that the Luftwaffe’s fighter planes were then well able to escort German bombers on their short trip across the Channel. The realisation of what destructive power aircraft could wield in any future conflict forced the government to plan extensive civil defence measures and between 1931 and 1935 committees were set up to consider air-raid precautions. Estimates of likely casualties were high. One particularly pessimistic Air Ministry report predicted that enemy planes would drop 100 tons of high explosives on the first day, 75 tons on the next and 50 tons a day from then on for a month (in contrast a mere 300 tons had been dropped on Britain during the whole of the First World War). Her lifelong friend Pam Board recalls her father going into the garden when Bristol was being bombed. The skies would light up with incendiaries and, having no air-raid shelter, they hid under the kitchen table. |

||||||||

|

||||||||

| Trixie Kirk, now in her nineties, recalls that it was so light in Broad Street with the incendiary bombs that came down that you could read a newspaper. It is important to realise that at the outbreak of war the country had no unified, centralised fire brigade, but myriad local forces under the control of dozens of County Councils. Axbridge Rural District Council was the fire authority for Wrington and all calls in respect of outbreaks of fire in the Wrington District had to be made there. If they were busy, calls were transferred to Cheddar. At this time, Wrington’s Brigade was run as an auxiliary service and, just like the many other civil defence organisations established at this time, was manned by volunteers. |

||||||||

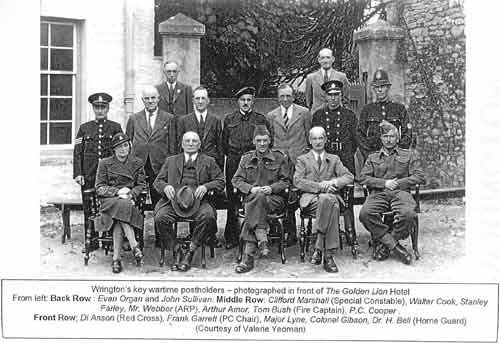

| In June W.J. Egan, Fire Brigades' co-ordinating officer for the RDC, wrote to the Parish Council inviting their co-operation. Egan was a real asset to the district. Before arriving in Axbridge, he had had a wealth of experience as a practical fireman in large city brigades and was a capable lecturer in many subjects closely allied to fire-fighting, such as fire salvage, gas, high explosive and incendiary bombs. He had joined the service as a salvage man in the Liverpool Fire Salvage Corps in 1919, after being released from the Royal Navy in which he had served as a physical training instructor on board HMS. Furious, the first aircraft-carrier to land a plane at sea. Later on in the war he was promoted to the post of Commandant, Area Training School Number 17 fire force area. During 1939 the Fire Authority had been considering the provision of a central fire station and large engine at Winscombe. Two other villages, East Brent and Wrington, were to have a large tender, with small tenders in various other parishes. Egan came to Wrington to inspect potential premises and make an appeal for men. The building eventually adopted was the old coach house adjoining the John Locke Rooms, to this day still affectionately known as “The Old Fire Station.” Chairman of the Parish Council at the time, Frank Garrett, approached local builder and Police Special Tom Bush to ask him to form a village fire-fighting force. Tom willingly agreed and set about enlisting volunteers. Founder members included Gilbert Cousins, Fred Hollier, Reg Kelly and local builder and undertaker Howard Yeates. Many years later Tom declared that this was one of the most rewarding achievements of his life and none who benefited from the firemen’s dedication and bravery would argue with that. |

||||||||