|

Wrington Website: Trevor Wedlake's Writings A Traveller's Tale |

|

Wrington Website: Trevor Wedlake's Writings A Traveller's Tale |

|

First published here May, 2004 |

Like many another, my old friend Cecil decided with his wife, in their mid-thirties, to up sticks and take their two young sons off to Canada to seek new life and opportunity there. Now, in the last years of his eighth decade, he is still there: his two sons are regular all-Canadian guys with few memories of the old country. When his wife died in 1990 Cecil brought her mortal ashes back to inter them in the Mendip hills above Langford in North Somerset, where she had grown up and attended St Mary's church. Nearly every year since he has returned for a few weeks' holiday. Though, as he says, half his life has been lived in Canada and travelling in the United States, he remains unrepentantly English: his accent is as the day he emigrated and no americanisms feature in his conversation. |

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

| He flies from Canada to Amsterdam, and Amsterdam to Bristol. "What I like about that route," he says, "is that on the approach to Lulsgate I can see the house where I'm going to stay, and I know that soon I'll be drinking a cup of English tea, and within hours, a pint of English beer." While he's here, besides drinking English tea and beer, he loves to explore old Bristol, and though not a churchgoer, he never tires of standing and wondering at the architecture of ancient churches and cathedrals. |

|||||||||||||

| At Blagdon Cecil had found the schoolmaster rather tough, but when he got down to Burrington the strictness paid off, and he soon topped the school, especially in arithmetic. Burrington had no real playground and playtime was spent in the village square; when a car came occasionally the teacher blew a whistle and the pupils ran to the roadside. Among the fondest memories he has of the 1930s are of his unofficial school holiday rides on the footplate of the Wrington Light Railway engine. Cecil spent many long summer days with his paternal grandmother at Blagdon, who lived close to the station and was caretaker of it. |

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

| Cecil and Jean, Churchill, 1929 | |||||||||||||

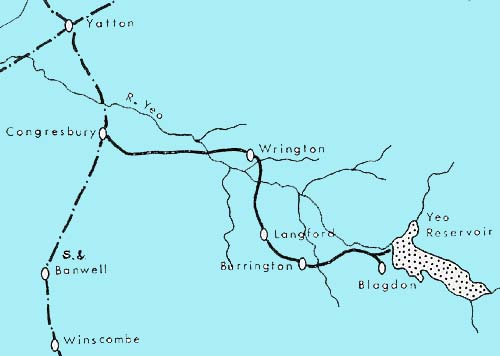

| The stationmasters at Blagdon, Burrington and Langford had been withdrawn at the end of 1925, as traffic reduced, and Mr Gait, the Wrington master, became responsible for the whole line. The Wrington Light Railway, which ran just over 6 miles from Congresbury to Blagdon, opened in 1901, didn't run beyond Wrington after 1950, and closed altogether in 1963. On some carefree holiday mornings when the engine had completed its shunting, Cecil's grandmother would give him his breakfast, an egg wrapped in a handkerchief, and a thick slice of bread, and off he'd go to join the driver Mr Oliver Oliver (Oliver Twice) or Mr Fred Flower and the fireman to have his fry-up with them, cooked on a gleaming shovel in the engine firebox. No one, but absolutely no one, he claims, can know how good a fresh egg tastes who hasn't had one fried on a railway fireman's shovel ! After breakfast, when the train was loaded with the large 17 gallon milk churns for which Blagdon was an important pick-up point for local farmers, and a variety of produce and other commodities, they made ready for the return to Congresbury. Cecil watched carefully as the driver pulled the whistle cord and opened the regulator. The safety valve shut down with a click as the steam entered the cylinders, and with some puffing and clanking the station buildings began to slide backwards. Driving this little train on its single track was probably not too exacting a job, but to a 10 or 11 year old, the driver was a figure of authority and his attention seldom strayed from the little cab window. The top speed of 25 mph compares favourably with the maximum permitted speed of 20mph for lorries in the '30s. On the way down to Burrington the line crossed an embankment above the level of the fields and the grazing sheep and cows, and on down the 1 in 70 gradient over Rickford Brook, and reduced speed to 10mph for the ungated crossing at Bourne Lane, and into Burrington, whose office walls were lined with best-kept-station awards. From Burrington they rattled down the steepest section of 1 in 50 to Langford. In the steep banks here on either side of the track, with the first soft murmurings of spring, came the primroses to slay the winter's gloom, and the cowslips and the dandelions which children never picked, and a myriad gold stars of the little unsought celandines. |

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

| At Langford the line crossed the A38; the crossing gates could be seen thrown aside decades after the line closed. Here the boy always had to keep out of sight in the tender. Was it because the station master was about ? From Langford the line crossed a little bridge over a mill stream, over a 'cattle tunnel', across the Blagdon Yeo, and on round the gentle curve into Wrington. Again the driver closed the regulator and opened the drifting valve, and they coasted into Wrington, past the cast-iron 'gents' and the yellow corrugated parcel-shed and hissed gently to a stop. Here Cecil said goodbye to the crew and ran along the platform and up Station Road to his maternal grandparents, who kept a general store and hardware business at the top of the street. |

|||||||||||||

| The Parsley name goes back centuries in Wrington; a family vault dated 1706 is in the centre aisle of the parish church. Cecil's maternal uncles spent the whole of their working lives delivering hardware and paraffin to all the surrounding villages and hamlets. |

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

| It was behind the large paraffin storage tanks that he hid the small bombs he'd unearthed playing on the Mendips early in the war. Grandfather Parsley was not impressed with this hiding place and the home-guard were called very hurriedly. After some days amusing himself in the warehouse and seeking out Wrington acquaintances, Cecil would decide to return to Blagdon. He'd present himself to the crew of the morning down train, and be welcomed aboard. He was always sad as they left Rickford and chugged up to Blagdon which meant journey's end; but he knew that on the morrow, or some imminent, gold-capped morning, fishing, tadpoling, birdsnesting permitting, he would ride that snorting iron horse again. |

|||||||||||||